Ebola disease: causes, symptoms, treatment, and prevention

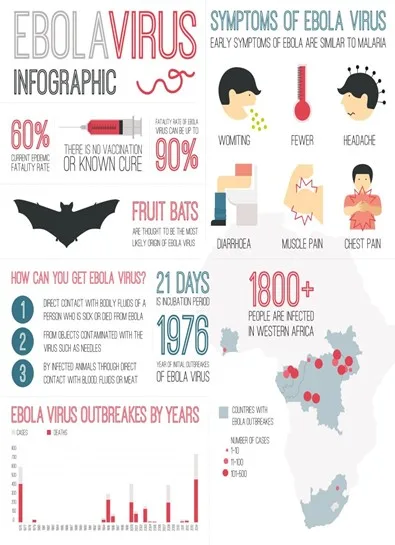

Ebola virus disease (EVD) is an uncommon but fatal disease marked by a sudden onset of fever, severe weakness, muscular pain, headache, and sore throat. Ebola is spread by direct contact with the blood, bodily fluids, and tissues of people and nonhuman primates. As a life-threatening infection, critically unwell patients require intense supportive treatment. Unfortunately, exposure to infected fluids while caring for a sick person allows Ebola to spread quickly. Symptoms might appear anywhere from 2 to 21 days following Ebola infection.

This virus, named after the Ebola River, first emerged in Sudan and the Democratic Republic of Congo in 1976 and has just lately spread beyond Africa. Despite its presence for more than 35 years, the greatest epidemic occurred in West Africa in March 2014, and cases have subsequently decreased dramatically. Having said that, there is still a risk of future outbreaks, therefore understanding more about the deadly virus will help prevent its spread.

Ebola is one of numerous viral hemorrhagic fevers caused by infection with a virus from the Filoviridae family, and the fatality rate varies according to strain. For example, Ebola-Zaire has a mortality rate of up to 90%, but Ebola-Reston has never killed a human.

Ebola at a glance:

- The average Ebola case mortality rate is around 50%. With that said, case mortality rates in previous epidemics ranged from 25 to 90%, depending on the various conditions and how early the infection was diagnosed and treated.

- At the moment, there is no Ebola vaccine, but many are being developed. The World Health Organization has financed research on various possible vaccines, and one of them, the Ebola ca Suffit vaccine, demonstrated 100 percent effectiveness in a study involving 4,000 patients in Guinea.

- Ebola is classified as a zoonotic virus since it is transmitted to people by animals; yet, infected humans may also transmit it to one another. The Ebola virus most likely originated in African fruit bats, although many other species can spread the infection through blood and other fluids.

How to tell if I have the Ebola disease?

Ebola is a virus from the Filoviridae family, also referred to as Filovirus, and it causes a very high fever as well as heavy bleeding both inside and outside the body. Symptoms might emerge as soon as two days after exposure or up to three weeks later. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reports that symptoms most frequently manifest 8 to 10 days after exposure.

The most prominent and noticeable indication of the Ebola virus is acute exhaustion, but there are many more. Laboratory tests may reveal low white blood cell and platelet counts, as well as increased liver enzymes. Here are some of the symptoms of the Ebola virus disease:

- Fever

- Cough

- Hiccups

- Red eye

- Diarrhea

- Vomiting

- Headache

- Sore throat

- Difficulty breathing

- Difficulty swallowing

- Unusual lack of appetite

- Severe physical weakness

- Chest and abdominal aches

- Internal and external bleeding

- Joint and muscular discomfort

It is important to note that as long as the patient’s blood and secretions retain the virus, they are contagious. In fact, the Ebola virus was identified from the sperm of an infected man 61 days after the emergence of the disease. So, if you’ve recently come into touch with someone afflicted with Ebola or have handled contaminated animals, you should be on the lookout for any of the symptoms listed above. If this is the case, get medical treatment right once.

What causes Ebola?

Ebola can be further split into subtypes that correspond to the place in which they were first discovered. These include Bundibugyo, Reston, Sudan, Taï Forest (formerly known as Ivory Coast), and Zaire.

People in Africa have contracted Ebola from handling infected animals that were discovered unwell or dead, including the following species that can transfer the virus through blood and bodily fluids:

- Gorillas

- Monkeys

- Porcupines

- Chimpanzees

- Forest antelopes

The good news is that, unlike most other viruses, the Ebola virus cannot be spread via the air or by touch alone; it must be transferred directly through contact with a sick person or animal’s body fluids. If you know someone who has it, you should avoid any contact with their blood, breast milk, diarrhea, saliva, semen, feces, perspiration, urine, semen, and vomit.

The bad news is that healthcare personnel are particularly susceptible to getting Ebola since they frequently work with the blood and body fluids of infected people. Ebola virus sickness can spread through the eyes, nose, mouth, damaged skin, and sexual contact. It may also arise as a result of contact with infected animals or things, such as needles and personal belongings like toothbrushes.

What doesn’t cause Ebola?

Ebola cannot be transferred by the air, food, or water, or through contact with Ebola survivors. You should be cautious, however, because Ebola remnants have been found in the sperm of survivors up to three months after recovery. There is also no evidence that Ebola may be spread by bug bites, such as those caused by mosquitos.

How is Ebola diagnosed?

Ebola may closely resemble other diseases, such as the flu, malaria, typhoid fever, and HIV/AIDS, particularly in its early stages. To diagnose Ebola, clinicians first determine if an outbreak is ongoing and whether others in the patient’s vicinity are at risk. Because Ebola spreads quickly through human-to-human contact, this may be an excellent starting place for a diagnosis.

Second, healthcare professionals will carry out blood tests to find Ebola virus antibodies. Blood tests can show important information such as low platelet counts, extremely low or high white blood cell counts, abnormal clotting factor levels, and increased liver enzymes.

If someone is believed to be infected with Ebola, they may have to undergo a three-week quarantine. If no symptoms emerge within 21 days, Ebola can be confidently ruled out.

Important similarities and distinctions between Ebola and HIV/AIDS

The director of the CDC, Dr. Tom Frieden, stated in 2014 that “In the 30 years I’ve worked in public health, the only thing like this has been AIDS. We need to act quickly to prevent this from becoming the world’s next AIDS.”

The Ebola virus and HIV are quite similar. Both are viruses that originated in Africa, both are carried by host animals and subsequently transmitted to people, both are dangerous if left untreated, and neither has an effective vaccine despite years of research.

It’s vital to remember that viruses don’t always transmit through the same bodily fluids. According to the CDC, HIV is only spread by blood, breast milk, or sexual intercourse. In addition to these, Ebola may also be transmitted by urine, saliva, perspiration, feces, and vomit. These fluids must come into touch with damaged skin or mucous membranes, such as the eyes, nose, or mouth, in order to infect someone. Ebola is somewhat more spreadable than HIV, but significantly less transmissible than more prevalent illnesses such as the flu.

What are the treatment options for Ebola?

Unfortunately, there is currently no vaccine at hand for Ebola. As of the writing of this article, several vaccinations are being tested and while none are ready for clinical use, researchers are optimistic given that a vaccine called Ebola ça suffit was proven to be fully effective in a study involving 4,000 patients in Guinea.

However, rigorous supporting measures are in place to guarantee an Ebola patient’s comfort and fortitude. These measurements include the following:

- Administering blood products as required.

- Regulating the patient’s fluids and electrolytes.

- Keeping other infections and dehydration at bay.

- Keeping the patient’s oxygen and blood pressure at an appropriate level.

The potential vaccines for Ebola

In October 2014, the World Health Organization (WHO) held an expert consultation to evaluate, examine, and eventually license two possible Ebola vaccines (with the last step still undone):

- GSK plc, a British multinational pharmaceutical firm, worked with the US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIH) to create the cAd3-ZEBOV vaccine. It employs a chimp-derived adenovirus vector with an Ebola virus gene added.

- rVSV-ZEBOV was created by the Public Health Agency of Canada in Winnipeg in collaboration with NewLink Genetics, an Ames, Iowa-based firm. The vaccine contains a weakened virus found in animals, with one of its genes swapped with an Ebola virus gene.

In February 2017, the Lancet, a highly regarded publication, released the full results of a study that demonstrated the full effectiveness of the Ebola ca Suffit vaccine on 4,000 patients in Guinea. This trial raised the researchers’ expectations for a vaccination that not only works but can be made accessible rapidly in sufficient quantities to protect key frontline workers and influence the epidemic’s future evolution.

Prevention

As we all know, the best way to treat a disease is to prevent it. To avert transmission, we can take precautions such as:

- Providing all healthcare professionals with adequate protective attire.

- Isolating Ebola patients from interaction with unprotected individuals

- Regularly disinfecting hands with soap and water or an alcohol-based hand sanitizer.

To prevent an Ebola epidemic, everyone in the community must work together. People should avoid touching clothing, accessories, and medical equipment that has been in contact with someone infected with Ebola. Healthcare staff must segregate Ebola patients and wear protective gowns, gloves, masks, and eye shields while doing so. Cleaning workers should use a bleach solution to clean floors and surfaces that may have come into contact with the Ebola virus.

Ebola spreads swiftly across families and among friends once they are exposed to contagious fluids whilst caring for a sick person. This is why persons at risk of Ebola should be hospitalized and cared for by trained specialists. In hospitals, thorough cleaning and correct disposal of needles are critical for preventing additional infection and slowing the spread of an outbreak.

Complications

Complications are fairly prevalent after recovery. Given that everyone’s immune systems are unique and react differently to illnesses, some people will continue to feel the symptoms for weeks or even months following recovery. These long-term consequences include but are not limited to, chronic weariness and weakness, sensory alterations, liver and eye inflammation, hair loss, psychosis, and joint discomfort.

In addition, there are potentially fatal complications, such as multiple organ failure, coma, and severe external and internal blood loss. The reasons for these issues and the number of them to be aware of are currently being investigated.

Conclusion

The WHO has indicated that the average death rate for an Ebola infection is 50%. However, as previously stated, the various strains of the virus have a greater or lesser likelihood of death. To make matters worse, the CDC believes that Ebola survivors will retain antibodies to the virus for more or less ten years. This implies that if you have had the virus before, you have not necessarily become immune to it.

If you find yourself in an unsafe circumstance, it is critical to be careful. The earlier the infection is detected, the better the prognosis for infected people. Until a vaccine is available in sufficient quantities, everyone must exercise caution to prevent the spread of Ebola and a possible epidemic.

Tags: Ebola virus , Ebola virus preventions, Ebola virus tretment,Ebola virus precaution tips,Ebola virus remedies,Ebola virus drugs,Ebola virus trement in europe,Ebola virus dosage,Ebola virus medicine